Quicken the Sense of Public Duty

December 16, 2016

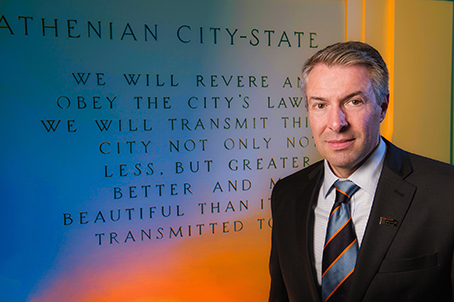

Maxwell’s new dean, David M. Van Slyke, takes the Athenian Oath very seriously. And he views the Maxwell School — with all its complexity and plurality and disciplinary cross-currents — as uniquely prepared to uphold it.

Here’s what David Van Slyke wants you to know about him: He may be a public administration guy, but he has a holistic view of the Maxwell School. He believes the School’s greatness is not in spite of its unique and unusual combination of interdisciplinary undergraduate and professional education, but is dependent on it. He takes the mission as a school of citizenship and public affairs to heart, and looks to that core value as he seeks to guide the school forward.

“We are not a monolithic place. Our complexity is one of our real strengths. But telling that story and making that visible is also one of our greatest challenges,” he says.

Six months in as the 10th dean of the Maxwell School, Van Slyke is ruminating over the mission of the school and his role leading it. “For too long too many people have viewed the Maxwell School as a public administration school, fueled by our number-one ranking,” he says. “That’s a great asset, and public administration is an outstanding department of scholars, staff, and students, but there are many other amazing elements to the School.”

He offers community geography as an example — an enterprise based in the geography department, but relying on collaboration with colleagues in Political Science, Economics, and Sociology to address issues of migration and assimilation. “The synergies harvested are amazing,” he says. “Geography students can work with a political scientist who studies citizenship, looking at ways to get new immigrants to assimilate that are both respective of their own cultures and identity but also receptive to the ideals of their new country.”

“Our strength,” he says, “lies in our interdisciplinary base, which strengthens and informs both the research we do and the accessibility and relevance of that research to decision makers.”

When Van Slyke took the helm of the Maxwell School in July, he became the first dean to come out of the faculty ranks since Guthrie Birkhead in 1977. That’s pretty impressive for a first-generation college student who had zero aspiration for an academic career.

Van Slyke grew up in New York’s Hudson Valley in a family of modest means. “My parents knew very few people who went to college, and certainly no one in academia,” he says.

With an undergraduate degree in economics, he went to work managing projects for an infrastructure company. After a couple of years, his company sent him to a young leadership program that awakened an unforeseen interest in public service. Van Slyke decided to switch gears and moved to a state agency that, shortly thereafter, spun off into a freestanding nonprofit. In both iterations, he was managing teams, projects, resources, and working with client groups.

He also went from working 80 hours a week to half that, leaving time to further develop his skillset. He considered going into law or business, but grew increasingly intrigued about the intersections between policy, politics, and markets. With a possible academic career in mind, he pursued and earned a PhD in public administration from SUNY Albany.

Van Slyke researches on the policy implications of public-private partnerships — not only the how-to’s of such arrangements, but their broader meaning for governmental effectiveness. He is also a thoughtful student of terms such as citizenship and public service, and how devotion to the public good plays out across sectors and throughout a life course.

His first faculty appointment was at the Andrew Young School of Policy Studies at Georgia State University, where he became friendly with colleagues Arthur Brooks and Ross Rubenstein, who left for the Maxwell School in 2002 and 2003, respectively. Van Slyke followed in 2004. “To join one of the top institutions in my field and also be back in proximity to family was an opportunity I couldn’t pass up,” he says.

Over the next dozen years at Maxwell, Van Slyke steadily rose through faculty ranks to full professor, then the endowed Bantle Chair; he served as department chair and associate dean, before being named dean. He distinguished himself both for his teaching — he’s a two-time recipient of the Birkhead-Burkhead Award and Professorship for Teaching Excellence — as well as his scholarship. He is director and fellow of the National Academy of Public Administration, co-editor of two top journals in his field, and author of Complex Contracting: Government Purchasing in the Wake of the U.S. Coast Guard’s Deepwater Program (Cambridge University Press, 2013).

Van Slyke says he has a “deep love and affection” for the Maxwell School. When he tells you he’s humbled to serve as dean, you believe it.

He’s clearly drawing from his professional background managing projects and teams and his research on government relationships to involve all of Maxwell’s constituencies, both internal and external.

“When people feel like they have a voice, they’re more invested in what they do. I want our faculty and staff to be excited about coming to the Maxwell School every day,” Van Slyke says.

He’s spent the last six months doing a lot of listening. “I’m not afraid to make decisions, but I’m a great believer in stakeholder engagement,” Van Slyke says.

He’s met with every single department chair, program director, center and institute director, the Maxwell School staff, advisory board, a few hundred Maxwell alumni and donors, and has regular interaction with Karin Ruhlandt, dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, and SU Provost Michele G. Wheatly, all as part of an effort to work collaboratively with faculty, staff, students, and alumni to refine the vision of the Maxwell School moving forward.

“If our students feel invested as ‘owners’ of a Maxwell experience, I believe they will carry that with them as they become alumni,” he says. “If we continue to engage with them regularly, even early in their post-Maxwell careers, then we are more likely to enjoy their time, wisdom, experience, and generosity at any stage.”

While he has no interest in a top-down approach, David Van Slyke does have an internal compass guiding him to strengthen what he considers the Maxwell School’s core value, namely public service.

Van Slyke casually recites the Athenian Oath verbatim, evidence of his sincere commitment to the concept of working toward making something better than you found it, whether that’s the city and state or your local library or house of worship. It’s a concept Van Slyke says applies far beyond government service. “The School has a unique mission and commitment to educating leaders who will be outstanding citizens and engage in public service throughout their lives, regardless of where they work and live,” he says.

“By trying to establish a broader context for public service, we go beyond being looked at as a school that only trains government bureaucrats. Our students don’t all end up as civil servants and there may be other ways for them to make contributions in the private or nonprofit sectors, consistent with these kind of values.”

One of Van Slyke’s goals is to create experiential learning opportunities that partner undergraduate and graduate students with faculty experts, so as to leverage the School’s interdisciplinary strengths in solving real-world organizational and community challenges.

He points to dire poverty rates in the city of Syracuse as a possible example. “We could bring an interdisciplinary research team — political scientists, geographers, sociologists, historians, anthropologists, economists, experts in housing and health policy — to analyze this through multiple lenses and catalyze that into problem solving and options to be tested.”

The idea is to create a vibrant student learning experience that not only teaches students analytical skills from a broad perspective, but also provides experiential opportunities to test those skills. And at the same time, “maybe some of those will bear fruit in a way that will have transformational opportunities within the community,” Van Slyke says.

When he refers to “community,” he doesn’t just mean Syracuse, but communities throughout the world that are touched by faculty research and the work of Maxwell alumni.

One of Van Slyke’s favorite experiences in his 12 years teaching at Maxwell has been his involvement with the Mandela Washington Fellows Program, which for the last three summers has brought 25 young leaders from countries all across Africa to the School for an intensive leadership program. “These students are so intellectually curious and engaged. They ask some of the hardest questions. And they are so committed to going back and making a difference,” says Van Slyke.

Many of these students have expressed interest in returning to the Maxwell School for graduate degree programs but are hindered by the cost. “It’s part of my responsibility to tell that story and find donors and organizations and foundations that want to support the goals of our school and those students,” says Van Slyke.

A generation from now, there will be dozens of Africans who returned to the continent with a Maxwell experience. “It will take many years, but I have no doubt we will see positive changes happening on rule of law, on reductions in corruption, on health and economic status,” he says.

In other words, Africa will find itself not only not less, but greater and more beautiful than it was transmitted to these young people. Says Van Slyke, “If the Maxwell School can play a role, then we are fulfilling our mission.”

Surprisingly International

Look closely, and you’ll discover that Maxwell is a campus leader for globalism.

Decades ago the perception of Maxwell training practitioners to run domestic government was mostly accurate. But today Maxwell is international — in its scholarship, its community, and its impact.

At a time when Syracuse University is pressing a strategic plan with a pillar devoted to internationalization, David Van Slyke, Maxwell’s new dean, says the School stands in good stead. “As a global institution,” he says, “we have the intellectual expertise, the alumni commitment, and the institutional reputation to be leaders in all aspects of our work.”

A third of the Maxwell School’s 160 faculty members focus on research that is exclusively outside of the United States, including experts on every continent in the world. (Van Slyke himself has engaged in executive education and training in China, India, Russia, Singapore, Thailand, and the Netherlands, and participated in a World Bank project with the Russian government.) He says even faculty who don’t have a specific international focus conduct research that has international portability, helping shape the way policy makers and decision makers look at issues. That’s not to mention the thousands of Maxwell alumni working in business, NGOs, and governments across the globe.

Van Slyke’s vision of citizenship, sitting at the core of Maxwell’s identity, is far from domestic. “We are a global institution,” he says. “Citizenship is relevant beyond our own borders.”

By Renée Gearhart Levy

Related News

School News

Dec 2, 2025

School News

Oct 13, 2025