Feeding the Next Generation

July 27, 2021

Catherine Bertini has guided many students to the World Food Programme, the United Nations organization honored with a Nobel Peace Prize.

Less than an hour’s helicopter flight northwest of the Haitian capital Port-au-Prince is the town of Anse Rouge, where the coastal landscape is a patchwork of squares, white mounds and tropical vegetation. Salt farming is the subsistence livelihood that Haitians eke out here; it is backbreaking, sweltering labor, whose low pay means it is mainly women doing the work. The conditions are such that the women are frequently plagued by health problems caused by dirty water and unsanitary conditions. And, the hurricanes that regularly blow through often wipe out any meager investments.

By planting trees, building canals, erecting retaining walls and using improved salt harvesting methods, development experts and aid workers hope that they can make the effort more sustainable, more profitable and healthier, particularly for women who toil there.

In the thick of the effort is the World Food Programme

(WFP), the United Nations agency whose work helping to alleviate hunger and

build resilience around the world earned a Nobel Peace Prize late last year.

And one of many of those intimately involved in the program’s work in Haiti

last spring was Meghan Sullivan ’17, a graduate of the Maxwell School’s master

of arts in international relations program.

In the thick of the effort is the World Food Programme

(WFP), the United Nations agency whose work helping to alleviate hunger and

build resilience around the world earned a Nobel Peace Prize late last year.

And one of many of those intimately involved in the program’s work in Haiti

last spring was Meghan Sullivan ’17, a graduate of the Maxwell School’s master

of arts in international relations program.

Speaking from her home in Port-au-Prince in early April, Sullivan says there’s no way she would be doing what she’s doing if it hadn’t been for Maxwell. “Maxwell really opened doors for me that wouldn’t have been opened otherwise,” she says. “I’m from a farming family in rural, Upstate New York. The U.N. is not a place that I thought I would end up when I was younger. It’s those relationships that Maxwell had, and the preparation that Maxwell gave me, that made all of this possible.”

Sullivan, in fact, is one of several alumni who found their calling—the place to put their Maxwell theories into practice—through the WFP.

Catherine Bertini, professor of practice emeritus, is largely to thank for that. She headed the WFP for a decade, between 1992 and 2002, serving under former Presidents George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton and George W. Bush, and was the U.N.’s undersecretary general in New York for three years before she joined Maxwell.

“We were thrilled when Catherine Bertini joined the Maxwell faculty. Her expertise, gained from incredible life experiences, was a tremendous asset to our students, particularly those who felt a calling to humanitarian policy and development work,” says David M. Van Slyke, dean of the Maxwell School.

“She took a special interest in her students’ success, pointing several of them toward the World Food Programme for internships, thereby creating a pipeline between Maxwell and the United Nations that has launched the careers of several of our alumni.”

A SYMBIOTIC RELATIONSHIP

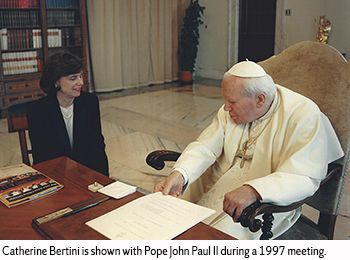

The photos on Catherine Bertini’s website offer a snapshot

of what it might have been like to lead the World Food Programme. In one, she

pours food into a bowl held by a youngster in Zimbabwe. In another, she walks

hand-in-hand with two children in Rwanda. Other images show her in much

different environs: Sitting, for instance, next to Pope John Paul II during a

1997 meeting, and three years later, shaking hands with then-United Nations

Secretary General Kofi Annan. Still another has her seated at a long table in

the White House, along with President George W. Bush, for a 2001 talk about

Afghanistan.

The photos on Catherine Bertini’s website offer a snapshot

of what it might have been like to lead the World Food Programme. In one, she

pours food into a bowl held by a youngster in Zimbabwe. In another, she walks

hand-in-hand with two children in Rwanda. Other images show her in much

different environs: Sitting, for instance, next to Pope John Paul II during a

1997 meeting, and three years later, shaking hands with then-United Nations

Secretary General Kofi Annan. Still another has her seated at a long table in

the White House, along with President George W. Bush, for a 2001 talk about

Afghanistan.

It has indeed been a storied career. Bertini was the first U.S. citizen to head the WFP, and she is credited with helping transform the agency’s operations with actions that no doubt helped set it on a trajectory toward last year’s Nobel Peace Prize.

During her tenure, she assisted millions of victims of wars and natural disasters throughout Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and parts of eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union.

In recognition of her work, she received the World Food Prize, known as the “Nobel Prize for Food and Agriculture” in 2003. Rather than accept the prize money, she established a trust that provides grants to local organizations around the world that improve access to training and education for women and girls.

Three years later, when she joined Maxwell, Bertini saw an opportunity for a symbiotic relationship. While the WFP could benefit from the support of Maxwell’s graduate students, the students themselves would have yet another means to gain invaluable experience and fulfill a degree requirement—international relations students must complete an internship abroad.

Students who attained internships with the WFP say her support was vital, though Bertini downplays that. “I gave advice to students on how to get internships,” she says. “They took it from there.”

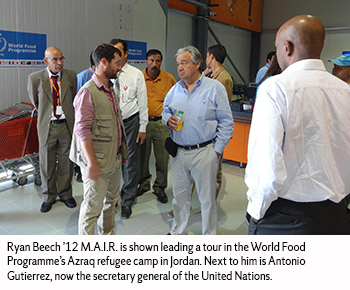

In one case, a regional director for the WFP asked Bertini

to recommend two interns to help as an influx of Syrian refugees moved into

Jordan. She offered up two top students, Edgar Luce ’12 M.A.I.R. and Ryan Beech

’12. Following those Beech, who received a master of arts in international relations,

was hired by the WFP shortly after his internship.

In one case, a regional director for the WFP asked Bertini

to recommend two interns to help as an influx of Syrian refugees moved into

Jordan. She offered up two top students, Edgar Luce ’12 M.A.I.R. and Ryan Beech

’12. Following those Beech, who received a master of arts in international relations,

was hired by the WFP shortly after his internship.

He worked in Jordan for five years, gained field-level experience in cash and voucher programming and then moved to the organization’s headquarters in Rome where he is now a programme and policy officer. He develops guidance, strategies and learning materials and provides direct support to field offices.

“While I dreamed of working for institutions like the United Nations, even in high school, I never thought I would have that opportunity, or at least I couldn’t see a clear pathway to it,” he says, pointing back to Maxwell and his former professor, Bertini.

Her legacy can be seen in the organization even at a technical level, Beech says. At the WFP, Bertini focused on empowering women. “A key part of our strategy for cash and voucher programming is to give money directly to women while focusing on their greater financial inclusion, access to financial products and services and economic empowerment,” he says. “I run into WFP staff all the time who reflect positively on the period that she served as executive director.”

Back at Maxwell, Bertini also encouraged student Emily Fredenberg ’16 M.P.A./M.A.I.R. Her internship was part of the United Nations Network for Scaling Up Nutrition Secretariat, hosted by the WFP in Rome.

As was the case with Beech, it turned into a career.

Before ending up in the Rwandan capital Kigali, where she

has been the WFP’s head of external partnerships and communications for Rwanda

since 2019, Fredenberg first spent several years in Beirut, Lebanon, helping

the organization as it dealt with the influx of refugees fleeing the

devastation of the Syrian Civil War.

Before ending up in the Rwandan capital Kigali, where she

has been the WFP’s head of external partnerships and communications for Rwanda

since 2019, Fredenberg first spent several years in Beirut, Lebanon, helping

the organization as it dealt with the influx of refugees fleeing the

devastation of the Syrian Civil War.

In the chaos of human suffering and scale of the efforts by the WFP and other organizations trying to feed, clothe and shelter people fleeing Syria, Fredenberg says she couldn’t have managed there if it weren’t for her Maxwell classes: simulations, for example, that got students to grapple with real world scenarios in a classroom setting.

“That was one of those moments when we’re responding to a humanitarian crisis and here I am on the ground, the one doing this thing, thinking ‘These simulations, this is what actually happens in real life,’” says Fredenberg.

PRIDE IN THE PIPELINE

While working in Haiti in late April, Meghan Sullivan received word of a new opportunity with the United Nations, a post that would bring her back home to the States and allow her to put more focus on development, an interest she discovered while studying at Maxwell and working with the World Food Programme.

Sullivan was offered a highly competitive position as associate programme management officer in the U.N. Secretariat’s Department of Economic and Social Affairs. In simple terms, the position provides support to development projects “to enhance the capacities of developing countries” in priority areas, she explains, adding, “It is the right step for me at the right time, and I’m excited to be working in international development and to see how another part of the U.N. system works.”

Bertini, meanwhile, spends some of her time in her hometown of Homer, New York, while also frequenting Chicago, where she serves as a distinguished fellow at the Chicago Council on Global Affairs.

She retired from Maxwell four years ago, around the time a fellow World Food Programme alumnus joined the faculty as a professor of practice. Masood Hyder joined public administration and international affairs in 2017 and offers courses on humanitarian action, food security, the U.N. and development aid, no doubt pulling from his experiences providing aid to places like Sudan, Bangladesh, North Korea, Iran, Indonesia and Djibouti. “Masood brings a depth of field experience, human understanding, and a history of creative and compassionate leadership to his classes,” says Bertini. “We are so fortunate that the WFP legacy continues on the Maxwell faculty.”

Bertini has maintained the Maxwell connection, continuing to teach part-time. A signature class: A week-long intersession in which students get an up-close look at the inner workings of the U.N. in New York City.

This past fall, as the school and the rest of the world grappled with the fallout from COVID-19, Bertini taught online about the U.N. Though virtual and remote learning has its drawbacks, she said she was able to capitalize on the medium by bringing in more outside guest presenters. And she had her students watch the U.N. General Assembly livestream.

Bertini enjoys hearing updates about former students like Sullivan. She takes pride in watching the pipeline she helped nurture: of Maxwell graduates heading out into the world, with the WFP or other humanitarian organizations.

“My retirement package is to sit back and take pride in watching the career successes of so many Maxwell graduates,” she says.

By Mike Eckel with reporting by Jessica Youngman

Published in the Summer 2021 issue of the Maxwell Perspective

Related News

Media Coverage

Feb 3, 2026

School News

Feb 2, 2026

Media Coverage

Jan 23, 2026