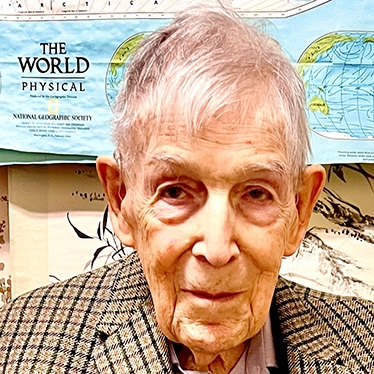

In Memoriam: Frederick D. Marquardt

August 20, 2025

‘Outstanding Scholar of History’

Frederick D. Marquardt was known for his high expectations—and for his tough grades.

In evaluations, his students often commented on his strict grading, some even lamenting that obtaining the coveted “A” felt nearly impossible. And yet, the same reviewers often shared that Marquardt was the best professor they’d experienced at Syracuse University.

In his nomination letter for Marquardt’s appointment as a Maxwell Professor of Teaching Excellence, history department colleague Norman Kutcher wrote, “Comments extolling his undergraduate teaching abound in his evaluations, coupled almost always with grudging appreciation for his refusal to compromise standards. A student in a research seminar called him ‘the most difficult, yet fairest teacher I have ever had.’”

Kutcher, professor of history and Laura J. and L. Douglas Meredith Professor for Teaching Excellence, shared in sorrow with longtime colleagues upon learning that Marquardt passed away after a battle with cancer on July 10. He was 85 and had been living in North Carolina, near his sister, Anita, and her spouse, Tom Toth.

Having earned a Ph.D. from the University of California in 1973, Marquardt taught first at the University of Michigan and then in the Maxwell History Department until his retirement, when he was granted emeritus status. He was an expert on German social history with a special interest in the history of German workers and catechisms, the texts that were used to instruct young Catholics in church doctrine.

“Fred was an outstanding scholar of history, an award-winning teacher and a mentor to many,” said Kutcher. “As a historian, he expected utmost intellectual rigor, and asked questions which made you consider the broader significance of your findings. Fred was a delight to talk with about your research because he could help you see connections that otherwise eluded you.”

Marquardt’s graduate students often shared that he never let an uninformed opinion go unchallenged and expected them to come to seminar highly prepared. One wrote, “His questions always went directly to the heart of the issue at hand and his examination of a topic never wavered until all of the central points were raised.” The same student said his mentorship through the dissertation process was “nothing short of amazing, displaying a devotion to his discipline and his students going far beyond what was called for.”

Marquardt was proud that some of his students were awarded prestigious fellowships and obtained post-docs and published their dissertations with highly regarded university presses. Undergraduates in his research seminars also benefitted from his individualized attention to their work: Nearly every year that Syracuse participated in the Phi Alpha Theta (history honor society) regional conference, one of his students received a “best paper” prize, said Kutcher.

The eldest of two children, Marquardt grew up in a working class family near Pittsburgh. His parents were born in Germany, and while the family spoke English at home, Marquardt decided to learn to read, write and speak German on his own. He graduated top of his high school class and went to Princeton on a scholarship, interested in law and history.

“Fred could and would discuss events of German history with great detail and passion,” said his brother-in-law, Tom Toth, adding that he’d spent many years researching and writing two books that he never published, in part because of his own perfectionism and pursuit of additional knowledge on the subjects.

Toth said Marquardt especially enjoyed visiting archives in Berlin for his work, and in his spare time, loved to read, attend cultural events and listen to classical music. “He most loved to teach and spoke often about his students and friends that shared his passion,” he said.

By Jessica Youngman

Published in the Fall 2025 issue of the Maxwell Perspective