One Korea

December 23, 2009

How a collaboration in public management and information technology hints at the peninsula’s political future.

The guests at this informal meal, at Mok Hwa restaurant on South Crouse Avenue, hesitated to mingle. On one side were visiting North Korean computer scientists. They stared across the table at several Maxwell School graduate students, all from South Korea.

They stared across the hostilities resulting from the peninsula’s separation after World War II. They stared across an economic gap that has produced an average GDP per person in the North of $1,800, in the South of $27,600. They stared across the gap that has produced an average life expectancy of 67.3 years in the North, 78.6 in the South.

The North Koreans were in Syracuse as part of an ongoing collaborative initiative between the University and Kim Chaek University of Technology in Pyongyang. The project’s director is Stuart J. Thorson, Maxwell School professor of international relations and political science. The meal was his idea.

“There was initially much suspicion,” Thorson recalls. “Each country had for many years been demonized in the other.

“After a bit of food and perhaps a sip of soju” — the vodka-like distilled beverage native to Korea — “they began to talk and realize that, while non-trivial political differences may separate their countries, they are all Koreans,” Thorson says. “While I had expected that things would ultimately go well, I was surprised at the speed with which the dinner conversation became friendly and quite good-humored. Shared culture and language were able, at least over the course of the meal, to bridge a deep ideological chasm. It was heart-warming to experience.”

The information technology exchanges conducted between Syracuse and Kim Chaek during the first half of this decade and the relationships nurtured since have allowed North Korean scientists and their Syracuse counterparts to develop trust. In this sense, Thorson says, the research exchange has important implications for more traditional forms of diplomacy, increasing his confidence about diplomatic relations between North Korea and the United States and eventual peace on the peninsula.

“I’m optimistic,” Thorson concludes. “It’s a solvable problem.”

Stuart Thorson is Maxwell’s first Donald P. and Margaret Curry Gregg Professor — a faculty post created earlier this year to focus specifically on Korean affairs. (See related article.) Thorson’s naming to this professorship recognizes nearly a decade of collaboration with Korea by a team he heads.

The Syracuse-Kim Chaek exchange is the only academic exchange between American and North

Korean universities. Seven times in five years, North Korean scientists visited Syracuse for research collaboration on information technology (IT). Six times, the Syracuse team met with its North Korean counterparts in North Korea or China. The exchange enhanced IT capability in North Korea and provided an area of cooperation between the United States and North Korea, a necessary step toward reconciliation, says Thorson.

To get the project started, the University consulted, in 2001, with the Korea Society — an organization based in New York City that promotes understanding and cooperation between the United States and Korea — and approached North Korea’s United Nations mission to discuss possible joint academic engagement. The American government has been consulted throughout the program.

“No matter what people say, the Koreas will unite someday.”

The first North Korean delegation visited Syracuse in March 2002, and Syracuse sent a scientific delegation to Pyongyang that June. Nearly four years of work culminated when North Korea’s first digital library, using open-source software, opened at Kim Chaek in January 2006. The library’s resources were used to help broadcast the New York Philharmonic’s concert in Pyongyang two years later.

A Regional Scholars and Leaders Seminar program began in August 2005, with added participation by China and South Korea. RSLS sessions continued in Beijing in 2006 and 2007, concentrating on information sharing and language and presentation skills needed to conduct international scientific meetings.

In 2006, Syracuse and the Korea Society started preparing undergraduate teams of North Korean computer scientists for their first international science competition, the Association for Computing Machinery’s annual programming contest. In its second year of competition, a Kim Chaek team that had worked with Syracuse faculty members reached the finals.

And in 2007, this U.S.-North Korean exchange led to the establishment of the U.S.-DPRK Scientific Engagement Consortium, to explore collaborative academic scientific activities.

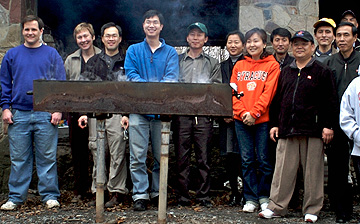

As they worked on IT issues, North Korean scholars also shared everyday experiences, learning about life in Central New York. They saw football games in the Carrier Dome, Syracuse Chiefs baseball games, and a Big East basketball tournament at Madison Square Garden. They picnicked at Green Lakes State Park in Fayetteville.

The North Koreans learned the meaning of Easter and taught their hosts why their biggest national holiday is April 15, celebrating the birthday of Kim Il-sung, their country’s founder.

These scientific exchanges are expected to resume this academic year, Thorson says. The U.S.-DPRK Scientific Engagement Consortium is organizing a delegation, including Syracuse representatives, to visit North Korea to talk about science and policy infrastructure and mutual research areas. (Other efforts are stalled. Two years ago, Kim Chaek scholars were to visit Syracuse under a junior faculty development program, but so far none have been permitted to come, largely due to the political climate. It’s not always easy to pioneer understanding across political and ideological boundaries.)

The Syracuse-Kim Chaek exchange is indicative of a long-standing engagement in Korean affairs centered at Maxwell, where Koreans have studied for more than 70 years. The faculty includes experts in Korean governance, history, politics, and security. Recently, the School announced the creation of the Korean Peninsula Affairs Center, to consolidate this expertise around the study of the future of the relationship between North and South. Says Dean Mitchel B. Wallerstein, KPAC will provide an opportunity “to think in much more systematic ways about the political, economic, and social issues associated with reunification.”

Korea, an independent country from the 7th until the 20th century, became a protectorate of imperial Japan after the Russo-Japanese War and was annexed by Japan in 1910. World War II ended Japanese occupation but did not restore Korean independence. Instead, the United States partitioned Korea at the 38th parallel to discourage the Soviet Union from overrunning the entire peninsula.

“With the division of the peninsula, the U.S. virtually created a ‘Korea problem,’” says George Kallander, assistant professor of history and expert on Korea, who is on research leave this semester at the Academy of Korean Studies in South Korea. “Koreans themselves did not have a problem. Their country had never been divided like this before.”

He points out the importance of Korean pride and tenacity. “The division of the peninsula was unprecedented and no Korean wanted it. Korea has at various times in the past used foreign forces to overcome domestic political and military problems, but always, always, always Korea has prevailed. This period of division is an anomaly and will not last.

“No matter what people say, the Koreas will unite someday.”

The 1945 partition set the stage for today’s high-stakes diplomacy over North Korea’s nuclear weapons. In April of this year, North Korea withdrew from the Six-Party Talks on nuclear disarmament and has since taken steps to restart its plutonium reprocessing facility and tested a weapon.

Jongwoo Han, an adjunct professor of political science and an expert on Korean politics, traces the evolution of the North Korean weapons program to 1991, when the Soviet Union’s collapse changed the balance of power in Asia and made relationships with America much more important. North Korea began to develop its nuclear strategy as a bargaining chip to gain recognition from the United States.

“North Korea knows its regime security is guaranteed only if the United States recognizes it,” says Han, the co-leader of the exchange program with Kim Chaek University. He came to the Maxwell School to pursue a doctorate in political science, which he received in 1997. He and Thorson researched the impact of information and communications technologies on governance. They concentrated on Korea.

In 2002, a North Korean diplomat told Han, “We are going to go all-in” in playing the nuclear development card to gain recognition from the United States, as Han wrote in a 2009 article in the Australian Journal of International Affairs. He explained, “Pyongyang has pursued nuclear proliferation primarily in order to attain security and economic aid,” a point the late South Korean President Kim Dae-jung made in 2007 as he hosted visitors from Syracuse.

Han’s article quoted Kim: “Every one of Pyongyang’s moves has always been politically motivated and strategically calculated. North Korea Chairman Kim [Jong-il] thinks only America is capable of providing the military security and large-scale economic aid his country needs.”

Maxwell faculty members who study North Korea tie a final, formal end to the Korean War — and the end of the North’s nuclear aspirations — to this single goal: North Korea’s achievement of full diplomatic relations with America.

Thorson, who anticipates “a dramatic increase in political unity on the Korean peninsula,” identifies two steps the United States can take toward diplomatic relations with the North: helping negotiate a formal end to the Korean War and opening an interest section — not an embassy, but a center of American operations — in Pyongyang. (The armistice of July 27, 1953, ended the war’s fighting, but was never signed by South Korea. There is no peace treaty.) Says Thorson, “we should be starting with issues on which trust can be built and work up to the most challenging issues. We’re trying to solve the most difficult issue first’’ — that being the North’s nuclear weapons program.

Yet both he and Han are optimistic.

“I hope the smooth inter-Korean cooperation keeps going on economic, cultural, and social issues” while the nuclear issue is being resolved, says Han.

As a former deputy assistant secretary of defense, Dean Wallerstein was involved in negotiating the 1994 Agreed Framework with North Korea on the cessation of plutonium reprocessing (which the DPRK later abrogated). In his view, the steps toward full relations are: an agreement on denuclearization, a Korean War peace treaty, and the demobilization and withdrawal of miltary forces from the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), where currently more than one million North Korean troops are massed.

“The sine qua non is denuclearization,” he says, although there are “enormous problems of verification.” Wallerstein points out, for example, that North Korea had dug thousands of tunnels north of the DMZ where weapons are concealed.

Ambassador Donald P. Gregg, for whom Thorson’s new post is named, was the U.S. Ambassador to South Korea from 1989 to 1993. He foresees direct negotiations between the U.S. and North Korea within a year. In an upcoming article in The Ambassadors Review, Gregg writes that the U.S. should forgo thoughts of regime change and pursue negotiations, both bilateral and in the Six-Party Talks, to end the North’s nuclear weapons program in exchange for full U.S. relations and a formal end to the Korean War.

“I think North-South unification is inevitable, but neither side wants it to happen quickly, as a result of either implosion or explosion in North Korea,” he says. Or, as Han phrases it, all parties “should seek a soft landing, not a hard landing.”

The transition of power from Kim Jong-il, who reportedly had a stroke in 2008, remains a concern. He is now said to favor his youngest son, Kim Jong-un, who has no prior experience in government or international affairs. Han sees the senior Kim walking a tightrope: “The military power in North Korea, in general, does not want to negotiate with the U.S., while Kim Jong-il has attempted to normalize the relationship with the U.S. Thus, he was trying to address the concerns of both military and foreign policy teams by taking an all-in approach with nuclear weapons and engagement with the U.S.” The question, says Han, is whether Kim can continue his foreign policy and pass power to his son.

Gregg identifies the young Kim as a key player: “Both sides look for a gradual process of accommodation, which is why I feel that young Kim, educated in Switzerland, is such a potentially important figure.”

However, “no one really knows how the North Koreans think about all this,” Wallerstein says, “given their proclivity for self-isolation and self-reliance.”

He poses a series of questions:

“What are the dynamics within the North Korean government? How ill is Kim? How capable is his youngest son? What will the military hardliners do in a period of transition? There’s so much uncertainty.”

He concurs with Gregg’s reunification timetable of about 20 to 30 years, anticipating “a gradual evolution toward reunification, beginning with security confidence-building measures.”

One winter’s day Thorson drove the North Korean researchers through the hills southeast of Syracuse. They drove past two towering buildings set back from the road. One man asked about them. It’s senior citizen housing, Thorson explained.

“What does that mean?”

It’s a place where older and retired people can live with their peers and are provided special services, Thorson replied.

“You mean they don’t live with their families?”

The North Korean’s surprise that elderly Americans don’t live with their children offered Thorson insight into the two cultures.

“While there is no doubt that most elderly in the DPRK have a difficult life — what with food and medicine shortages — what fascinated me in the comment was simply the glimpse into the more relationship-based Korean culture and the important ways it differs from our more individualistic one,’’ he says.

It is hoped this long-term Syracuse-Kim Chaek exchange can help model diplomatic negotiations that may finally bring peace to the Korean peninsula.

Says Thorson, “Empathetic understanding comes from exposure, and this is one of the values of academic exchanges.”

By George S. Bain

Related News

School News

Jan 7, 2026

School News

Dec 5, 2025

School News

Dec 4, 2025