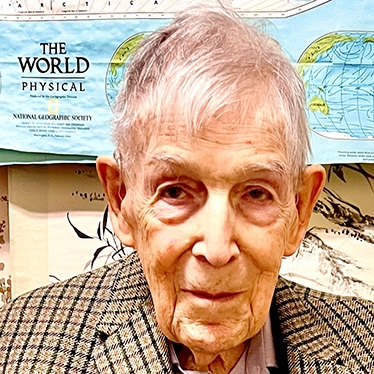

In Memoriam: John Burdick Remembered for Teaching, Advocacy

August 19, 2020

Syracuse University Today

Throughout his life, and particularly in his work as a cultural anthropologist, John Burdick was a strong advocate for peace, social justice and social change.

As a professor of anthropology in the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs and College of Arts and Sciences for nearly 30 years, Burdick deeply engaged his students in working toward the betterment of communities and neighborhoods, from the west side of Syracuse to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. In all of his work he led by example—listening deeply and living his values.

Burdick died July 4 of cancer at age 61. He leaves a strong legacy of teaching and research at Syracuse University, of social change in the Syracuse community and of social justice in South America.

A native of Northampton, Massachusetts, Burdick was raised in Pontiac, Michigan. He earned a bachelor’s degree in history from the University of Michigan, a master’s degree in cultural history from Yale University and a doctorate in anthropology from the City University of New York. Burdick came to Syracuse in 1992 to teach in the Maxwell School’s Department of Anthropology.

Burdick’s teaching and research focused on the role of grassroots action in bringing about social, political and cultural change and on working to decolonize knowledge. He served as chair of the Department of Anthropology from 2012-17; associate director of the Program on the Analysis and Resolution of Conflicts (now PARCC); and he co-founded and led the Syracuse Social Movements initiative for 11 years.

“John was a devoted teacher who cared deeply about his students, the questions they sought answers to, the rigor of the education they received, and how they would use what they learned to contribute in productive ways to society and find purpose and meaning in their work,” says David M. Van Slyke, dean of the Maxwell School. “As a scholar, he was committed to ensuring that his work was viewed as having been collected and analyzed with objectivity understanding that the outcomes might then find many audiences beyond peer-reviewed outlets.”

Burdick worked on different projects in Brazil over the past three decades, and reached people around the globe through his books on race, religion, gender and politics in Brazil, including “Looking for God in Brazil: The Progressive Catholic Church in Urban Brazil’s Religious Arena” (University of California Press, 1993); “Blessed Anastácia: Women, Race and Popular Christianity in Brazil” (Taylor and Francis, 1998) “Legacies of Liberation: The Progressive Catholic Church in Brazil at the Start of a New Millennium” (Taylor and Francis, 2004) and “The Color of Sound: Race, Religion and Music in Brazil” (New York University Press, 2013). Burdick received Fulbright-Hayes awards for research in Brazil in 1995 and 2004.

A hallmark of Burdick’s life and legacy was his commitment to furthering peace and social justice, particularly on Syracuse’s West Side. He worked extensively with the Westside Residents Coalition (WRC), advocating for thoughtful, equitable and community-led betterment of the West Side neighborhoods. He was a key player in the creation of Gifford Street Community Press, providing West Side residents a platform to express their concerns about gentrification, police conduct and disability rights. He was also a longtime member of the Syracuse Peace Council.

In addition to his dedication to his students and his work, Burdick was involved in the Syracuse University community. He served on the University Senate and on many other committees. Among his honors from the University were the William Wasserstrom Prize for Outstanding Graduate Teaching, the Chancellor’s Citation for Excellence, the Service Through Peace Award and the Chancellor’s Inspire Award.

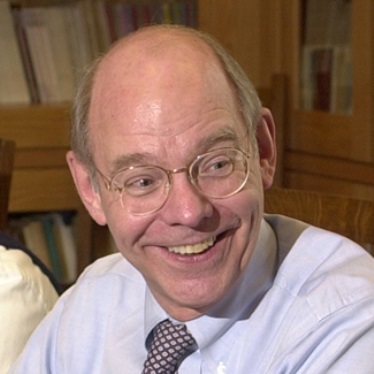

Robert A. Rubinstein, Distinguished Professor of Anthropology and professor of international relations, was the director of PARCC when Burdick began collaborating with the program in 1994. Through that collaboration Burdick combined his longtime commitment to justice with his teaching. He created the Community Engagement Fellows program, where students studied social change while working with social justice organizations focused on indigenous and immigrant rights and antigentrification work. He later developed the program into a minor focused on public advocacy.

Rubinstein says Burdick was a “consummate ethnographer,” one who insisted on good evidence and methodological rigor, and who taught his students how to achieve it when working in the community. He was a bridge builder who tried to bring people of opposing views to a consensus, and he listened deeply and thoughtfully to all he encountered. And he was deeply engaged in all he did.

“John was very meticulous—he scheduled his day in 15-minute increments and every moment was productive,” Rubinstein says. He often worked throughout the night, it was not uncommon to get emails from him at 2 or 3 in the morning.

“He was careful in providing feedback and was an excellent, caring and thoughtful mentor,” Rubinstein says.

“As a citizen and servant of the school and University, Burdick took seriously his goals of listening, learning and asking hard questions while treating people with respect and dignity,” says Van Slyke.

“His contributions are significant not only because of the many different forums in which he contributed, but because he also modeled leadership, humility, compassion and empathy, and curiosity,” he says. “I admired, respected and appreciated John as a faculty member, leader and friend and will miss him and his earnest intentionality to leave all that he found better than he found it.”

In 2012, Burdick developed “Helping the Poor Stay Put,” an international ethnographic study on the right to housing in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Burdick received a $597,000 grant from the National Science Foundation and the Economic and Social Research Council of the United Kingdom for the study, which originated from Burdick’s awareness of the growth of the housing rights movement and the growing crisis over housing in Brazil.

In a 2017 interview, Burdick said he hoped the project would be part of a long-term commitment by anthropology and social science to decolonize knowledge and to decolonize social science, to break down the notion that social science based in Euro-America has special privilege and knows how to understand the world in a better way than other ways of knowing.

Burdick built a strong multinational team to carry out the project, including housing activist Roberto Gomes dos Santos and filmmaker and videographer Emilie B. Guérette.

“John was and always will be an oasis in the middle of the desert, all these years using ethnography to better understand the human condition with all of her diversities, whether activists or not,” says Gomes dos Santos. “He taught me to pay attention to body language, listen deeply to the words of others and understand that social life is far more complex and contradictory than we may have thought. … His famous words and his teachings will be eternalized and passed on by each and every person who had the great opportunity to have absorbed his teachings and knowledge.”

“John Burdick was one of the most inspiring intellectuals and human beings I have ever had the chance to meet. I would always tell him how much I was learning just by watching him be and interact with others,” says Guérette. “He had the rare quality of listening, which he attributed to the techniques of ethnography, but I think was an innate gift of genuinely caring for others. He made everybody feel incredibly special. On top of being a brilliant and engaged anthropologist, he was a natural healer, truly moved by a desire for repairing injustices and positively transforming our world.”

Melinda Gurr G’17 earned a Ph.D. and performed postdoctoral work with Burdick in 2018. She worked with him on community organizing in Syracuse and studying the housing crisis in Brazil.

Gurr says Burdick prepared his students well for their futures in the world. “One thing he taught his students was to listen deeply, that it was an act of love and tuned in to the capacity of the human spirit,” she says.

He also led strongly by example. “He embodied profound social values—anti-racist, anti-capitalist and feminist—and lived those values,” Gurr says. “He truly walked the walk. I always thought, ‘This is the kind of person I want to be when I grow up.’”

Gurr says she is grateful for the lessons she learned from Burdick, including a very practical one. “Academics often write in an inaccessible fashion,” she says. “He forced me to get rid of the jargon and write differently. He taught me how to craft an argument.”

Those lessons will serve Gurr well as she begins a new role as an assistant professor at Southeast Missouri State University. “Three-quarters of the words I share with my students will come from him,” she says. “John’s impact lives on in so many ways through his students,” she says.

Burdick was asked in a 2017 interview what advice he has for students that are currently charting their course in the world. He offered his thoughts on why they should care about ethnography, which may seem to be obscure in a modern world.

“I think ethnography and getting good at it is at the heart of being a really good, effective member of society,” he said. “I think if you want to contribute in a good effective way—a sustainable way that expresses love and is part of your love for others, and where you really think you can make a good difference—then the ethnographic is a way of thinking, a way of being, a way of interacting.”

“I think that if we listen deeply, and if the kinds of techniques that we cultivate in ethnography can take hold, I think we can be much better at a lot of things,” he said.

Burdick is survived by his wife of 33 years, Judith Malkin; his children, Molly Malkin Burdick and Benjamin Malkin Burdick (Kara McCall); his parents, Dolores Burdick and Harvey Burdick (Jean Goddard) and his brothers, Albert Burdick (Diane Kinney) and Anthony Burdick (Kate).

A celebration of life event will take place on a future date.

For individuals who wish to make a donation in his memory, the family of John Burdick asks that you consider making a gift to the Maxwell Dean’s Restricted Fund. These gifts will be held in an account toward the establishment of a Fund in his honor that supports scholarships for cultural anthropology graduate students.

Published in the Summer 2021 issue of the Maxwell Perspective